About the Author

Learn about Dr. Michael Peters, a practicing optometrist and author of the sports vision book, See to Play. Get in touch for questions or more information.

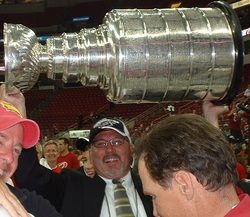

Dr. Michael Peters is a practicing optometrist at MyEyeDr (formerly of Eye Care Associates), based in Raleigh, NC. He attended West Virginia University for his undergraduate work and received his doctorate from Pennsylvania College of Optometry in 1988. After graduation, he started his sports vision specialty as a partner at Eye Care Associates and was the director of their sports vision program. He is the eye doctor for several area professional sports teams and continues to work with elite athletes and athletes in the Olympic, collegiate and amateur ranks. He has also lectured and published articles nationally on his work with athletes.

Dr. Peters’ stats:

- 1997 – 2016 – Carolina Hurricanes Team Optometrist

- 1998 – 2023 Tampa Bay Rays (AAA) playing for Durham Bulls

- 2017- present North Carolina Football Club

- 2017- present North Carolina Courage

- 2017 – present Milwaukee Brewers (A) playing for Carolina Mudcats

- 2011 – 2016 Carolina Rail Hawks Team Optometrist

- 2015 – 2017 Atlanta Braves (A) playing for Carolina Mudcats

- 2009 – 2011 – Cincinnati Reds (AA) playing for Carolina Mudcats

- 2012 – 2014 – Cleveland Indians (A) playing for Carolina Mudcatss

- 2003 -2016 USA National Baseball

- 2011 – 58th NHL All-Star Teams

- 2003 – 2004 – North Carolina State University – Director of Sports Vision program

- 2002 – 2008 – Florida Marlins (AA) (Carolina Mudcats)

- 1999 – 2002 – Colorado Rockies (AA) (Carolina Mudcats)

- 1991 – 1998 – Pittsburgh Pirates (A) (Carolina Mudcats)

- 1989 – 1997 Atlanta Braves (A) (Durham Bulls)

- Wakefield High School

Tar Heel of the Week: Michael Peters focuses on helping athletes see better

News and Observer, May 23, 2015

By Marti Maguire

Correspondent, RALEIGH

Michael Peters’ blurry eyesight gave him a clear vision of his future career at an early age.

His interest in improving athletes’ eyesight was piqued during his high school days, when he struggled to play basketball with bulky glasses, and was honed in his final days as a college linebacker and receiver who couldn’t focus on the ball.

“I literally hung up my cleats because I couldn’t see to play,” says Peters, an optometrist who heads the sports vision program at Eye Care Associates in North Raleigh. “I decided to be an eye doctor because I thought, ‘I can’t be the only one.’”

Peters has focused his career on exploring the tricky connection between vision and athletics, both by helping athletes to deal with poor vision and training others to improve their eyesight in ways that enhance their performance.

He is the team optometrist for the Carolina Hurricanes, the Durham Bulls and other teams, and has worked with professional football teams and Olympic athletes. He’s written a book, entitled “See to Play,” detailing his experiences working with athletes and his methods for improving vision.

Peters recently co-authored a set of guidelines for diagnosing and treating the damage to athletes’ vision caused by concussions, an emerging issue in professional sports. Based on a three-year study, that protocol was recently published in a peer reviewed trade journal, now open to doctors nationwide.

Jay Harrison, a former Hurricanes player who was treated with the new protocol, says Peters’ innovative solutions to vision problems are key in getting athletes like him playing again.

He also says Peters and other sports doctors are also helping to make these high stakes games safer by creating a better understanding of how concussions affect the brain.

“Dr. Peters is on the cutting edge of what he does, and he’s always thinking of how he can best serve athletes,” said Harrison, who now plays for the Winnipeg Jets. “He’s so determined. Every time he sees a little more and learns a little more, it snowballs into something new.”

NFL career thwarted, Peters moved around as a child because of his father’s job as an electronics salesman, but by high school the family had settled in a small West Virginia town – and Peters had settled on a dream of playing in the National Football League.

He played high school basketball, football and track, earning letters in all three. He played football at West Virginia University briefly as a walk-on. But at the higher level of college play, his vision problems were more difficult to overcome.

“The contacts they made back in the day didn’t stay in place, and the glasses didn’t fit under helmets,” he says. “I’d play without them and I couldn’t see a thing.”

He recalls a particular practice when he caught a pass thrown by Jeff Hostetler, who would go on to play with the New York Giants. Peters was thrilled to find the ball in his hand, but not so thrilled that his ill-fitting contact lens had gotten stuck under his eyelid during the play.

He decided to channel his frustration into a career as an optometrist. The Triangle was his first stop, thanks to an early internship, and he started building his own practice in Raleigh in the late 1980s.

It is a general optometry practice; he fits all kinds of clients with glasses and contact lenses. But his specialty has always been working with athletes.

The first team he worked with regularly was the Durham Bulls, and he would go on to work with the Atlanta Braves and several other major-league teams, as well as the Carolina Mudcats.

He started with the Carolina Hurricanes in the 1990s, and has been a regular presence both at their games and behind the scenes working with players ever since. He’s also worked with National Basketball Association trainers and players.

In addition to his more high-profile clients, he frequently treats young people who suffered concussions playing youth soccer or other sports, as well as adults whose vision was affected by car accidents.

“From my little office here in Raleigh, we have a nice national reach,” he says.

Training the eyes to seeThe idea that vision is a key component of athletic prowess has slowly gained credence over the decades that Peters has been in practice. Studies have shown, for instance, that elite athletes on average have much better vision than the general public.

Yet Peters says many players and coaches still discount the importance of vision.

“Eyes are still the most overlooked thing in sports,” he says.

Peters’ methods to improve vision evolved as he experimented with new techniques. At first he worked on developing exercises to help athletes improve hand-eye coordination. Later, he realized that eye movement was important, and started training his patients to train their eyes as they do other muscles.

Over the years, trainers and coaches started realizing the value of this work.

“They’re getting to know there’s a lot we can do to help athletes use their full potential,” he says.

His book, published in 2012, talks about aspects of vision that are important to sports but typically overlooked, such as the ability to focus quickly and block out visual noise.

The protocol he helped develop for vision problems caused by concussions involves a series of tests to identify the area of the brain affected, followed by targeted exercises.

Peters says the foggy vision, light sensitivity and other vision-related symptoms that often accompany concussions were traditionally treated with pain medications. By the mid-2000s, these problems were accepted as signs of a specific type of concussion, yet treatments varied widely.

He and his business partner, Jason Price, conducted a study of 137 patients over three years to develop ways to diagnose and treat vision-related concussions, focusing on therapy rather than medications or surgery.

Most of the exercises can be duplicated easily by any doctor without special equipment, which Peters hopes will allow them to be used in patients who aren’t professional athletes.

Peters says most of these problems aren’t actually in a person’s eyes, but in the signals sent from the inner ear and brain to the eyes.

“Most of your vision is all about your sense of space and time,” he says. “That’s what gets hurt in a concussion.”

He compares the brain’s healing process to a computer rebooting in “safe mode” after a trauma. But all of the extra stimuli the brain encounters delays this healing.

The methods he’s developed can speed that process along in athletes for whom each week is incredibly valuable, and can also promote healing that might not take place otherwise.

“The protocol is to figure out which part of the visual system is overloaded and start back at the basics,” he says.

See To Play is a sports vision book teaching athletes about developing their eyesight

We believe in the importance of rigorous training and dedication in sports. Every athlete needs to put in their best effort to become a dominant and powerful competitor in their sector. Factors like resistance, speed, and strength are vital, but sight can also drastically determine the future of a game match.

If you purchase a copy of See to Play, you’ll learn about the following seven measurable vision traits:

-Vision acuity

-Detailed vision zone (central vision)

-Extreme side vision (peripheral vision)

-Eye movement

-Eye focus

-Eye, hand, and body coordination

-Visual noise and mental preparation

We know every eye is different, so we want to provide you with the tools to develop your sight traits. Our experienced optometrist, Michael Peters, brings readers ways to identify, measure, and exercise their vision to become a more coordinated and precise competitor. We encourage you to subscribe to our blog and learn more about See to Play.

Browse our website, read our publication, and discover what our readers say. You’ll find recommendations from the NFL, NBA, and Major League Baseball. Please buy our book and share your opinion about it with your friends.